PhD Project: Simultaneity in interaction

Simultaneously

performing

several

activities

is

a

phenomenon

we

encounter

not

only

in

everyday

life

but

also

in

many

professional

situations.

This

Ph.D.

project

describes

the

conditions

under

which

people

can

perform

several

activities

simultaneously.

For

this

purpose,

a

system

of

structural

compatibility

of

multimodal

resources

is

developed

on

the

basis

of

43

qualitative

individual

case

analyses.

The

data

basis

is

provided

by

a

corpus

of

200

h

of

a

theater

rehearsal

process

recorded

with

video

cameras

and

mobile

eye-tracking

glasses.

The

analyses

revealed

that

humans

require

certain

structural

conditions

to

perform

more

than

one

activity

simultaneously.

Performing

multiple

activities

at

the

same

time

is

possible

if

participants

can

divide

multimodal

resources

among

the

activities

(structural

compatibility).

If

two

activities

require

the

same

resource

(e.g.,

gaze),

they

are

structurally

incompatible,

and

one

of

the

activities

can

be

paused

or

canceled

until

the

required

resource

is

available

again.

However,

if

a

situation

requires

that

several

activities

be

realized

simultaneously

despite

structural

incompatibility,

the

lack

of

a

resource can be briefly compensated through the help of interactional procedures, e.g., routinization, prioritization, and synchronization.

Relevance of the topic

Summary

The

pager

vibrates,

and

the

senior

physician

rushes

to

the

patient

-

cardiac

arrest!

Two

residents

and

an

anesthesiologist

she

has

never

seen

before

arrive

with

her.

“Prepare

everything

for

cardiopulmonary

resuscitation,”

she

calls.

She

routinely

puts

the

ventilation

mask

over

the

patient‘s

mouth

and

nose.

At

the

same

time,

she

calls:

“Chest

compression;

30-to-2.”

The

doctor

nods

briefly

and

begins

chest

compressions.

Now

she

has

to

concentrate

and

pay

close

attention

to

repeatedly

pumping

air

into

the

patient‘s

lungs

twice

with

the

resuscitator

after

the

doctor

compresses

the

patient‘s

chest

30

times.

At

that

exact

moment,

the

anesthesiologist

asks

which

tube

she

should

prepare.

The

team

leader

turns

to

the

anesthesiologist

and

points

to

the

object

she

is

looking

for:

the

one

there

in

the

drawer,

of

course!

When

the

team

leader

turns

back

to

the

patient,

she

has

missed

the

moment to ventilate. The oxygen level in the patient drops...

This

example

is

based

on

a

training

case

described

by

Pitsch/Krug/Cleff

(2020)

.

It

demonstrates

that

there

are

processes

that

can

be

easily

reconciled,

whereas

other

processes

can

lead

to

problems

if

they

are

performed

at

the

same

time.

What

are

the

conditions

under

which

a

person

can

perform

two

or

more

activities

simultaneously?

What

needs

to

be

changed

so

that

communicative

problems

(such

as

in

the

example

above)

do

not

occur

or

occur

as

infrequently as possible?

The

concept

of

multitasking,

which

is

prominent

in

society,

seems

to

provide

an

answer

to

these

questions.

In

everyday

understanding,

it

describes

the

ability

of

an

individual

to

manage

two

or

even

more

tasks

simultaneously.

As

a

psychological

concept,

however,

multitasking

focuses

primarily

on

cognitive

tasks

and

problems

that

arise

when

two

processes

are

mentally

incompatible.

In

examining

the

example,

it

is

questionable

whether

the

team

leader

was

really

cognitively

unable

to

answer

the

question

and

perform

ventilation

at

the

same

time.

Rather,

the

problem

seems

to

be

that

the

two

activities

require

different

attention

spans

and

hand

grips; the two activities are not cognitively incompatible but structurally incompatible in terms of coordinating with the anesthetist.

If

one

expands

one‘s

view

from

the

rather

individualistic

psychological

concept

of

multitasking

to

the

interactional

concept

of

multiactivity

in

(social)

interaction

research

(Haddington

et

al.

2014)

,

one

realizes

many

situations

in

which

people

engage

in

several

activities

simultaneously.

For

instance,

when

people

have

conversations

while

eating

dinner

together

(Egbert

1997)

,

when

a

group

mucks

out

(i.e.,

cleans

up)

a

sheep

stable

together

(Keevallik

2018)

,

or

when

a

person

consults

another

on

how

to

proceed

while

building

a

closet

(Krafft/Dausendschön-Gay

2007)

.

Looking

at

these

everyday

situations

in

terms

of

interactions

rather

than psychology raises the question:

Under what conditions can two or more activities be completed simultaneously, and when is it difficult to do so?

Structural Compatibility Model: On the difficulty of doing two things at once

So,

what

are

the

structural

conditions

of

concurrent

activities?

To

investigate

this

question,

it

is

useful

to

compare

several

cases.

For

this

purpose,

settings

in

which

a

fixed

group

of

people

comes

together

in

repeatedly

similar

situations

lend

themselves

well,

for

example,

during

theater

rehearsals.

For

this

reason,

in

my

Ph.D.

project,

I

set

up

several

cameras

in

a

rehearsal

room

and

audio-visually

recorded

all

31

rehearsals

of

a

professional

theater

production

company

in

Germany

from

different

perspectives

(

Krug/Heuser

2018,

Krug

2018

).

In

this

way,

I

captured

every

situation

in

which

the

participants

performed

multiple

activities

simultaneously;

in

total,

I

qualitatively

compared

43

cases.

But

how

can

one

determine

when

it

is

"difficult"

or

"easy"

for

interactors

to

coordinate

several

activities

simultaneously?

This

is

only

possible

when

the

researcher

comes

down

from

his/her

“ivory

tower"

to

eye

level

with

the

participants

because,

as

humans,

we

cannot

see

into

the

minds

of

others

and

are

dependent

on

their

(body)

language

to

confirm

their

understanding

of

an

action.

Thus,

it

only

becomes

clear

that

my

interaction

partner

has

understood

my

wave

as

a

greeting

when,

for

example,

he/she

also

waves

back.

This

participant

perspective

is

central

to

conversation

analysis

(

Schegloff

2007

).

Working

with

the

means

of

conversation

analysis

is

to

scrutinize

the

reciprocated

actions

realized

by

others

during

an

interaction.

In

this

manner,

the

coordination

of

actions

(

Deppermann

2014

)

reveals

how

and under which conditions interactants break off or pause one activity in favor of another.

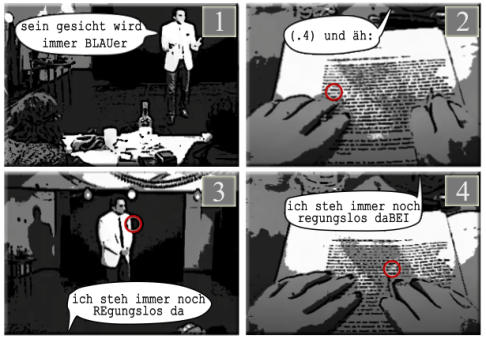

Figure 1: The actor interrupts his smartphone activity in favor of the greeting.

The

example

in

Figure

1

illustrates

how

something

like

this

can

unfold.

In

it,

an

actor

surfs

the

Internet

on

his

smartphone

at

the

beginning

of

a

theater

rehearsal

(image

1).

He

continues

to

do

so

even

when

the

dramaturge

of

the

production

enters

the

stage

and

wishes

the

actor

a

good

day

(“gu_n

TACH“).

Without

looking

up,

the

actor

reciprocates

this

greeting

with

a

hello

(“

MOIN

moin“)

(image

2).

Here,

the

actor

can

coordinate

his

two

activities

of

internet

surfing

and

greeting

in

such

a

way

that

he

can

perform

them

at

the

same

time.

This

is

possible

because

he

does

not

look

at

his

conversation

partner

during

the

verbal

greeting

but

keeps

his

gaze

(as

a

visual

resource)

directed

at

the

smartphone.

The

actor

implements

the

Internet

surfing

activity

here

by

holding

the

smartphone

with

one

hand

and

controlling

it

with

his

thumb.

From

this

observation,

which

seems

trivial

at

first

glance,

one

can

deduce

an

important

prerequisite

for

the

simultaneous

performance

of

several

activities:

the

body‘s

processes

(the

so-called

multimodal

resources)

must

not

interfere

with

each

other

when

they

are

used

for

different

activities.

They

must

be

structurally

compatible

with

each

other.

Unlike

chameleons,

which

are

able

to

look

in

different

directions,

humans

can

anatomically

select

only

one

gaze

target

at

a

time.

Thus,

in

order

to

realize

the

greeting

at

the

same

time

as

surfing

the

Internet,

the

actor

coordinates

the activities in such a way that he uses his gaze (visual resource) and his hand (haptic

resource)

for

surfing

and

only

participates

in

the

greeting

via

speech

(verbal

resource).

By

splitting

the

resources

between

the

activities

in

this

way,

the

actor

is

able

to

perform both activities simultaneously.

This

only

changes

when

the

dramaturge

expands

the

greeting

with

well?

(“na?“).

The

actor

responds

by

turning

his

gaze

from

the

smartphone,

looking

at

the

dramaturge,

and

also

responding

with

na?

(‘well‘?)

(image

3).

Thus,

the

actor

still

keeps

his

hand

on

the

smartphone

but

now

has

his

gaze

focused

on

the

greeting

in

addition

to

his

speech.

With

this

division

of

bodily

resources,

it

is

not

possible

for

him

to

continue

surfing

on

the

smartphone:

his

activities

here

are

structurally

incompatible

with

each

other.

However,

since

he

continues

to

hold

the

smartphone,

he

indicates

to

the

dramaturge

(and

all

other

participants)

that

he

will

probably

continue

his

surfing

activity

as

soon

as

his

visual

resource

becomes

available

again.

This

behavior

is

a

continuation

projection.

This

phenomenon

regularly

occurs

when

people

do

two

things

at

the

same

time

but

need

the

same

resource

(e.g.,

gaze)

for

both.

People

then

pause

one

activity,

here

web

browsing,

in

favor

of

another

(e.g.,

a

greeting).

Such

continuation

projections

of

paused

activities

always

involve

some

kind

of

"freezing"

a

currently

ongoing

process,

for

example,

holding

a

cup

just

in front of the mouth while speaking

(cf. Hoey 2018)

.

Since

the

dramaturge

expands

his

greeting

once

again

with

the

question,

“

How

are

you?”

(“

Wie

geht‘s

dir?“)

and

also

offers

his

hand

to

the

actor

(image

4),

the

greeting

now

requires

the

actor‘s

haptic

resource

in

addition

to

his

verbal

and

visual

ones:

he

can

now

no

longer

hold

the

smartphone

with

his

right

hand

and

decides

to

let

it

slide

onto

the

table

and

join

in

the

hand

greeting.

Thus,

no

physical

resource

now

remains

in

the

surfing

activity.

It

is

treated

as

aborted

by

the

interactants.

In

my

data,

it

appears

that

aborted

activities

are

more

difficult

for

interactants

to

resume,

which

is

why

participants

try

to

pause

activities

rather

than

abort

them.

The

example

shows

that

participants

can

simultaneously

coordinate

two

simultaneously

occurring

activities

if

they

use

the

resources

in

a

structurally

compatible

way.

If

activities behave in a structurally incompatible way, they are paused or aborted depending on the degree of incompatibility.

What

can

participants

do

when

a

situation

requires

that

two

structurally

incompatible

activities

not

be

aborted

or

paused

but

completed

simultaneously,

for

example,

during

resuscitation

as

in

the

introductory

example?

Such

situations

can

be

observed

regularly

in

theater

rehearsals

when

scenes

are

being

rehearsed.

In

order

not

to

have

to

start

from

the

beginning

with

every

forgotten

word,

one

of

the

participants

prompts.

This

means

that

if

an

actor/actress

is

stuck

in

the

text

(so

called

blanking

),

the

prompter

recites

the

correct

play

text.

This

requires

the

prompter

to

read

the

actors‘

performance

in

the

script.

How

does

a

prompter

recognize

that

an

actor

is

blanking?

In

the

analyses,

two

regular

features

emerge

in

this

regard.

First,

actors

often

pause

before

blankings.

However,

it

is

not

uncommon

in

the

theater

to

intentionally

insert

dramatic

pauses

to

intensify

the

play.

Thus,

secondly,

in

order

to

distinguish

a

dramatic

pause

from

a

blanking,

the

prompter

must

observe

the

performance.

Since

she

can

only

either

observe

the

play

or

read

along

in

the

script,

the

two

activities

are

structurally

incompatible

with

each

other.

Both

activities,

observing

and

reading

along,

require

the

gaze as a visual resource. How does a prompting person manage to observe the performance and simultaneously read-along, despite this structural incompatibility?

To

determine

this,

one

must

record

the

gaze

of

the

prompter.

This

is

achieved

via

so-called

mobile

eye-tracking

glasses,

which

record

the

view

of

the

person

wearing

them. A colored circular ring shows where the person is looking from a subjective perspective.

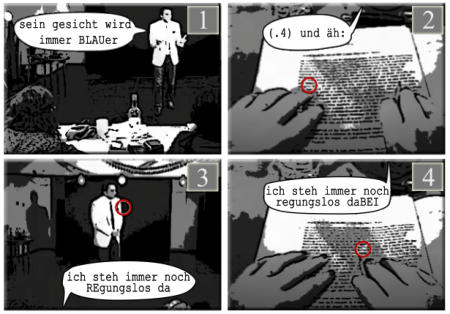

Figure 2: The assistant director prompts the actor. Image 1 shows the perspective of a camera behind the

director's table. Images 2-4 are taken from the eye-tracking glasses of the assistant director.

The

example

in

Figure

2

shows

the

prompter‘s

gaze

behavior

and

demonstrates

the

compensation

practices

with

which

the

prompter

(left

in

image

1)

deals

with

the

structural

incompatibility

of

the

activities

of

observing

and

reading

along.

In

doing

so,

she

reads

the

script

while

the

actor

(right

in

image

1)

acts

out

the

scene

on

stage

(image

1).

By

analyzing

the

prompter’s

eye-tracking

data

(images

2–4),

we

see

that

she

forms

a

kind

of

grid

with

her

hands

in

order

not

to

lose

her

place

in

the

script

(image

2)

and

reads

what

the

actor

says

in

the

script.

Suddenly,

the

actor

first

pauses

for

0.4

s,

and

then

utters

a

stretched

delay

signal,

äh

.

Since

this

is

an

element

that

is

not

recorded

in

the

script,

the

prompter

looks

up

at

the

actor

(image

3).

Here

she

can

observe

that

the

actor

is

frozen

in

his

play

and

has

stopped

moving.

She

interprets

this

not

as

a

dramatic

pause

but

as

a

situation

in

which

the

actor

is

stuck

in

the

text.

Since

this

must

be

avoided,

she

then

recites

the

missing

text

(“Ich

steh

immer

noch

regungslos

da“).

The

blanking

is

overcome

when

the

actor

picks

up

the

text

and

integrates

it

into

his

performance

(image

4).

At

this

moment,

the

prompter

re-lowers

her

gaze

into

the

script.

As

the

red

eye-tracking

circle

ring

shows,

her

gaze

lands

unerringly

on

her

pencil

as

part

of

the

grid.

This

helps

her

to

quickly

resume

her

read-along

activity

without having to search for the right line.

As

this

reconstruction

of

events

shows,

it

is

by

no

means

the

case

that

the

prompter

can

completely

resolve

the

structural

incompatibility

of

the

activities

of

observing

and

reading

along;

she

can

still

either

look

at

the

actor

or

read

the

script.

However,

she

resorts

to

practices

that

compensate

for

the

absence

of

the

visual

resource,

at

least

for

a

short

time.

For

example,

she

reads

along

in

the

script

until

she

gets

a

clue

about

a

text

blanking.

In

all

cases

studied,

these

cues

consist

of

the

pattern

pause

in

speech

and

stretched

delay

signal.

What

is

exciting

about

this

is

that

it

is

neither

a

prearranged

cue

nor

something

that

actors

learn

in

their

training.

Instead,

this

is

an

interactional

negotiation.

The

prompter

only

redirects

her

attention

from

the

script

to

the

actor

when

there

is

a

concrete

indication

of

a

blanking.

If

the

actor

blanks,

she

verbalizes

what

has

just

been

read.

This

means

that

the

prompter

not

only

reads

along,

anticipating

the

words,

but

is

also

able

to

repeat

an

entire

sentence

while

looking

at

the

actor.

In

this

way,

what

is

read

along

is

made

available

in

the

observation.

Since

the

prompter

immediately

resumes

her

read-along

as

the

actor

continues

in the text, she minimizes her time not doing so.

Accordingly, the coordinative action of the prompter is characterized by three procedures: a) routinization, b) synchronization, and c) prioritization.

a) Routinization:

With the help of the script, she can predict the course of the scene and the future utterances of the actors, which enables her to read along in

anticipation.

b) Synchronization:

While reading along with the performance, she looks at the parts of the text where the actor could potentially blank.

c) Prioritization:

She withdraws her visual resource from one activity for a minimally short moment only when there is a need for action in the other activity.

Through

these

procedures,

the

prompter

naturally

does

not

manage

to

grow

a

second

pair

of

eyes

or

learns

to

gaze

like

a

chameleon;

however,

she

can

compensate

for

the absence of the visual resource in such a way that none of the simultaneously relevant activities has to be interrupted or paused.

Possible applications

The

analyses

show

that

we

need

certain

structural

conditions

to

perform

more

than

one

activity

simultaneously.

Performing

more

than

one

activity

at

the

same

time

is

possible

if

we

can

divide

our

physical

resources

among

the

activities

(structural

compatibility).

If

two

activities

require

the

same

resource

(for

example,

the

visual

resource

gaze)

to

perform,

they

are

structurally

incompatible.

In

such

instances,

one

of

the

activities

can

be

canceled

or

paused

until

the

resource

is

available

again.

If,

however,

a

situation

requires

that

several

activities

be

realized

simultaneously

despite

structural

incompatibility,

the

lack

of

a

resource

can

be

compensated for briefly with the help of the interactional procedures—routinization, prioritization, and synchronization. This phenomenon is called "multiactivity."

As

the

example

of

the

prompter

demonstrates,

it

is

essential

that

she

have

recourse

to

these

techniques

in

order

to

be

able

to

pursue

her

task.

Accordingly,

the

question

arises as to whether this knowledge is limited to prompter situations or whether there are no other areas of application.

In

artistic

fields,

the

simultaneity

of

several

activities

always

plays

an

important

role

when

something

is

elaborated

while

it

is

being

done.

In

the

elaboration

of

scenes

(Krug

2020a)

,

something

is

performed

while

it

can

be

commented

on

and,

thus,

changed

at

the

same

time

(Krug

2020b)

.

The

simultaneity

of

activities

is

here

the

structural

precondition

for

creative

work.

Furthermore,

this

applies

to

many

didactic

areas:

in

dance

lessons,

a

dance

can

be

demonstrated

and

explained

at

the

same

time;

in

vocational

inductions,

a

machine

can

be

operated,

and

its

functioning

explained

at

the

same

time;

and

in

school,

an

experiment

can

be

demonstrated,

and

the

physical laws behind it explained. In all these examples, the simultaneity of activities is understood as an opportunity to communicate complex relationships.

But

what

happens

when

the

simultaneous

occurrence

of

activities

in

a

situation

poses

a

problem?

We

could

clearly

see

this

in

the

initial

example

of

the

resuscitation

situation:

here,

physicians

have

to

perform

several

activities

simultaneously,

which,

on

the

one

hand,

are

highly

time-critical

but,

on

the

other

hand,

are

not

always

compatible

with

each

other.

As

recent

studies

have

shown,

annually,

only

10%

of

the

approximately

700,000

people

who

suffer

cardiac

arrest

in

Europe

survive

resuscitation

(Gräsner

et

al.

2014)

.

Some

of

these

failed

resuscitation

attempts

are

due

to

problems

in

team

communication

(Castelao

et

al.

2013)

.

An

initial

study

by

Pitsch/Krug/Cleff

(2020)

shows

that

some

of

these

problems

occur

when

team

leaders

instruct

their

team

while

simultaneously

performing

an

often-complex

medical

intervention.

Since

the

activities

are

often

structurally

incompatible,

the

team

leader

faces

a

dilemma:

should

she

instruct

her

team

on

the

next

steps,

which

ensures

the

continuation

of

resuscitation,

but

thereby

risk

suspending

the

patient‘s

ventilation

for

a

short

period

of

time,

which

could

result

in

hypoxia

and

thus

permanent

damage?

In

the

worst

case,

the

team

leader

tries

to

meet

both

requirements

and

fails

twice:

an

improperly

instructed

team

can

prepare

resuscitation

measures

poorly,

and

a

failure to treat the patient can have fatal consequences.

Using

the

model

of

structural

compatibility

presented

here,

such

communicative

problems

can

be

systematically

identified,

described,

and

dealt

with.

Particularly,

the

model

can

support

medical

(and

other)

professionals

in

distributing

tasks

in

such

a

way

that

only

compatible

activities

have

to

be

realized

at

the

same

time.

The

model

thus

provides,

for

example,

a

structural

argument

for

the

fact

that

team

leaders

should,

if

possible,

not

perform

any

medical

hand

movements

but

should

concentrate

only

on

their

managerial

activities.

Hopefully,

this

knowledge

of

the

structural

compatibility

of

activities,

which

can

be

well

trained

in

medical

facilities,

will

contribute

to

save more lives in the future.

Project history

•

March to April 2016: audiovisual data collection at the theater

•

April to June 2016: Data preparation (synchronization, documentation, export)

•

September 2016: Presentation of first results at the GAL Congress in Koblenz ("Prompting in Theater Rehearsals. Co-

construction of play actions through multiactivity").

•

December 2016: Analysis and discussion of the data at RWTH Aachen University under the direction of Marvin

Wassermann ("Undressing in Interactions. Multimodal coordinations of multiple activities at the ‘edge‘ of theater

rehearsals").

•

April 2017: Data session at the workshop Seeing and Noticing - Videoanalysis in Action (V), Genres, Forms and Structural

Levels in Bayreuth ("Rehearsing in Theater Rehearsals as a Communicative Genre?").

•

June 2017: Presentation at the ICMC in Osnabrück ("Rehearsing in theatre: Collectively achieving an interactional

system by coordinating multiple activities").

•

July 2017: discussion of eye-tracking data in interactions at IPrA in Belfast ("Eye-tracking in theater: coordinating

multiple activities during a theater rehearsal").

•

November 2017: Start to work on a special issue on instructions in theater and orchestra rehearsals together with

Axel Schmidt, Monika Messner and Anna Wessel.

•

Juli 2018: Reflection on data collection at ICCA in Loughborough ("Collecting Audio-Visual Data of Theatre

Rehearsals. (Non-)Intrusive Practices of Preparing Mobile Eye-Tracking Glasses during Ongoing Workplace

Interactions")

•

September 2018: publication on how much my data collection disrupted the rehearsal process in Krug, Maximilian &

Heuser, Svenja (2018): Ethics in the field: research practices in audiovisual studies. In Forum Qualitative

Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(3), art. 8.

•

September 2018: Joint performance with Anna Wessel at the GAL Poster Slam in Essen wins the GAL Poster Award.

•

January 2019: Start of collaborative work with Anna Wessel on repetition in theater rehearsals as part of the

workshop Linguistic-communicative practices in the environment of art institutions. Multimodal and -medial perspectives on

public communication at Justus Liebig University Giessen ("Practices of Repetition in Theater Rehearsals").

•

January 2020: Submission of dissertation

•

August 2020: Defense of the dissertation (summa cum laude)

•

November 2020: Publication of Krug, Maximilian (2020): Erzählen inszenieren. Ein Theatermonolog als

multimodale Leistung des Interaktionsensembles auf der Probebühne. In: Linguistik online 104 (4), S. 59–81.

•

December 2020: Completion of work on the special issue on Instructions in theater and orchestra rehearsals

together with Axel Schmidt, Monika Messner and Anna Wessel. Included among others:

o

Krug, Maximilian; Messner, Monika; Schmidt, Axel; Wessel, Anna (2020): Instruktionen in Theater- und

Orchesterproben: Zur Einleitung in dieses Themenheft. In: Gesprächsforschung Online 21, 155-189

o

Krug, Maximilian; Schmidt, Axel (2020): Zwischenfazit: Sukzessive und simultane Verzahnung von Spiel- und

Besprechungsaktivitäten – eine Instruktionsmatrix für Proben. In: Gesprächsforschung Online 21, 264-277

o

Krug, Maximilian (2020): Regieanweisungen "on the fly". Koordination von Instruktionen und szenischem Spiel

in Theaterproben. In: Gesprächsforschung Online 21, 238-267

•

February 2022: Publication of the dissertation. Open Access!

Krug, Maximilian (2022): Simultaneity in interaction. Structural (In)Compatibility in

Multiactivities during Theater Rehearsals. De Gruyter. DOI (peer reviewed)

Open Access!

Simultaneously

performing

several

activities

is

a

phenomenon

we

encounter

not

only

in

everyday

life

but

also

in

many

professional

situations.

This

Ph.D.

project

describes

the

conditions

under

which

people

can

perform

several

activities

simultaneously.

For

this

purpose,

a

system

of

structural

compatibility

of

multimodal

resources

is

developed

on

the

basis

of

43

qualitative

individual

case

analyses.

The

data

basis

is

provided

by

a

corpus

of

200

h

of

a

theater

rehearsal

process

recorded

with

video

cameras

and

mobile

eye-tracking

glasses.

The

analyses

revealed

that

humans

require

certain

structural

conditions

to

perform

more

than

one

activity

simultaneously.

Performing

multiple

activities

at

the

same

time

is

possible

if

participants

can

divide

multimodal

resources

among

the

activities

(structural

compatibility).

If

two

activities

require

the

same

resource

(e.g.,

gaze),

they

are

structurally

incompatible,

and

one

of

the

activities

can

be

paused

or

canceled

until

the

required

resource

is

available

again.

However,

if

a

situation

requires

that

several

activities

be

realized

simultaneously

despite

structural

incompatibility,

the

lack

of

a

resource

can

be

briefly

compensated

through

the

help

of

interactional

procedures,

e.g.,

routinization,

prioritization,

and

synchronization.

Relevance of the topic

Summary

The

pager

vibrates,

and

the

senior

physician

rushes

to

the

patient

-

cardiac

arrest!

Two

residents

and

an

anesthesiologist

she

has

never

seen

before

arrive

with

her.

“Prepare

everything

for

cardiopulmonary

resuscitation,”

she

calls.

She

routinely

puts

the

ventilation

mask

over

the

patient‘s

mouth

and

nose.

At

the

same

time,

she

calls:

“Chest

compression;

30-to-2.”

The

doctor

nods

briefly

and

begins

chest

compressions.

Now

she

has

to

concentrate

and

pay

close

attention

to

repeatedly

pumping

air

into

the

patient‘s

lungs

twice

with

the

resuscitator

after

the

doctor

compresses

the

patient‘s

chest

30

times.

At

that

exact

moment,

the

anesthesiologist

asks

which

tube

she

should

prepare.

The

team

leader

turns

to

the

anesthesiologist

and

points

to

the

object

she

is

looking

for:

the

one

there

in

the

drawer,

of

course!

When

the

team

leader

turns

back

to

the

patient,

she

has

missed

the

moment to ventilate. The oxygen level in the patient drops...

This

example

is

based

on

a

training

case

described

by

Pitsch/Krug/Cleff

(2020)

.

It

demonstrates

that

there

are

processes

that

can

be

easily

reconciled,

whereas

other

processes

can

lead

to

problems

if

they

are

performed

at

the

same

time.

What

are

the

conditions

under

which

a

person

can

perform

two

or

more

activities

simultaneously?

What

needs

to

be

changed

so

that

communicative

problems

(such

as

in

the

example

above)

do

not

occur or occur as infrequently as possible?

The

concept

of

multitasking,

which

is

prominent

in

society,

seems

to

provide

an

answer

to

these

questions.

In

everyday

understanding,

it

describes

the

ability

of

an

individual

to

manage

two

or

even

more

tasks

simultaneously.

As

a

psychological

concept,

however,

multitasking

focuses

primarily

on

cognitive

tasks

and

problems

that

arise

when

two

processes

are

mentally

incompatible.

In

examining

the

example,

it

is

questionable

whether

the

team

leader

was

really

cognitively

unable

to

answer

the

question

and

perform

ventilation

at

the

same

time.

Rather,

the

problem

seems

to

be

that

the

two

activities

require

different

attention

spans

and

hand

grips;

the

two

activities

are

not

cognitively

incompatible

but

structurally

incompatible

in

terms

of

coordinating with the anesthetist.

If

one

expands

one‘s

view

from

the

rather

individualistic

psychological

concept

of

multitasking

to

the

interactional

concept

of

multiactivity

in

(social)

interaction

research

(Haddington

et

al.

2014)

,

one

realizes

many

situations

in

which

people

engage

in

several

activities

simultaneously.

For

instance,

when

people

have

conversations

while

eating

dinner

together

(Egbert

1997)

,

when

a

group

mucks

out

(i.e.,

cleans

up)

a

sheep

stable

together

(Keevallik

2018)

,

or

when

a

person

consults

another

on

how

to

proceed

while

building

a

closet

(Krafft/Dausendschön-Gay

2007)

.

Looking

at

these

everyday

situations

in

terms

of

interactions

rather

than

psychology

raises

the

question:

Under

what

conditions

can

two

or

more

activities

be

completed

simultaneously,

and

when

is

it

difficult to do so?

So,

what

are

the

structural

conditions

of

concurrent

activities?

To

investigate

this

question,

it

is

useful

to

compare

several

cases.

For

this

purpose,

settings

in

which

a

fixed

group

of

people

comes

together

in

repeatedly

similar

situations

lend

themselves

well,

for

example,

during

theater

rehearsals.

For

this

reason,

in

my

Ph.D.

project,

I

set

up

several

cameras

in

a

rehearsal

room

and

audio-

visually

recorded

all

31

rehearsals

of

a

professional

theater

production

company

in

Germany

from

different

perspectives

(

Krug/Heuser

2018,

Krug

2018

).

In

this

way,

I

captured

every

situation

in

which

the

participants

performed

multiple

activities

simultaneously; in total, I qualitatively compared 43 cases.

But

how

can

one

determine

when

it

is

"difficult"

or

"easy"

for

interactors

to

coordinate

several

activities

simultaneously?

This

is

only

possible

when

the

researcher

comes

down

from

his/her

“ivory

tower"

to

eye

level

with

the

participants

because,

as

humans,

we

cannot

see

into

the

minds

of

others

and

are

dependent

on

their

(body)

language

to

confirm

their

understanding

of

an

action.

Thus,

it

only

becomes

clear

that

my

interaction

partner

has

understood

my

wave

as

a

greeting

when,

for

example,

he/she

also

waves

back.

This

participant

perspective

is

central

to

conversation

analysis

(

Schegloff

2007

).

Working

with

the

means

of

conversation

analysis

is

to

scrutinize

the

reciprocated

actions

realized

by

others

during

an

interaction.

In

this

manner,

the

coordination

of

actions

(

Deppermann

2014

)

reveals

how

and

under

which

conditions

interactants

break

off

or

pause one activity in favor of another.

Figure 1: The actor interrupts his smartphone activity in favor of the greeting.

The

example

in

Figure

1

illustrates

how

something

like

this

can

unfold.

In

it,

an

actor

surfs

the

Internet

on

his

smartphone

at

the

beginning

of

a

theater

rehearsal

(image

1).

He

continues

to

do

so

even

when

the

dramaturge

of

the

production

enters

the

stage

and

wishes

the

actor

a

good

day

(“gu_n

TACH“).

Without

looking

up,

the

actor

reciprocates

this

greeting

with

a

hello

(“

MOIN

moin“)

(image

2).

Here,

the

actor

can

coordinate

his

two

activities

of

internet

surfing

and

greeting

in

such

a

way

that

he

can

perform

them

at

the

same

time.

This

is

possible

because

he

does

not

look

at

his

conversation

partner

during

the

verbal

greeting

but

keeps

his

gaze

(as

a

visual

resource)

directed

at

the

smartphone.

The

actor

implements

the

Internet

surfing

activity

here

by

holding

the

smartphone

with

one

hand

and

controlling

it

with

his

thumb.

From

this

observation,

which

seems

trivial

at

first

glance,

one

can

deduce

an

important

prerequisite

for

the

simultaneous

performance

of

several

activities:

the

body‘s

processes

(the

so-

called

multimodal

resources)

must

not

interfere

with

each

other

when

they

are

used

for

different

activities.

They

must

be

structurally

compatible

with

each

other.

Unlike

chameleons,

which

are

able

to

look

in

different

directions,

humans

can

anatomically

select

only

one

gaze

target

at

a

time.

Thus,

in

order

to

realize

the

greeting

at

the

same

time

as

surfing

the

Internet,

the

actor

coordinates

the

activities

in

such

a

way

that

he

uses

his

gaze (visual resource) and his hand (haptic

resource)

for

surfing

and

only

participates

in

the

greeting

via

speech

(verbal

resource).

By

splitting

the

resources

between

the

activities

in

this

way,

the

actor

is

able

to

perform

both

activities

simultaneously.

This

only

changes

when

the

dramaturge

expands

the

greeting

with

well?

(“na?“).

The

actor

responds

by

turning

his

gaze

from

the

smartphone,

looking

at

the

dramaturge,

and

also

responding

with

na?

(‘well‘?)

(image

3).

Thus,

the

actor

still

keeps

his

hand

on

the

smartphone

but

now

has

his

gaze

focused

on

the

greeting

in

addition

to

his

speech.

With

this

division

of

bodily

resources,

it

is

not

possible

for

him

to

continue

surfing

on

the

smartphone:

his

activities

here

are

structurally

incompatible

with

each

other.

However,

since

he

continues

to

hold

the

smartphone,

he

indicates

to

the

dramaturge

(and

all

other

participants)

that

he

will

probably

continue

his

surfing

activity

as

soon

as

his

visual

resource

becomes

available

again.

This

behavior

is

a

continuation

projection.

This

phenomenon

regularly

occurs

when

people

do

two

things

at

the

same

time

but

need

the

same

resource

(e.g.,

gaze)

for

both.

People

then

pause

one

activity,

here

web

browsing,

in

favor

of

another

(e.g.,

a

greeting).

Such

continuation

projections

of

paused

activities

always

involve

some

kind

of

"freezing"

a

currently

ongoing

process,

for

example,

holding

a

cup

just in front of the mouth while speaking

(cf. Hoey 2018)

.

Since

the

dramaturge

expands

his

greeting

once

again

with

the

question,

“

How

are

you?”

(“

Wie

geht‘s

dir?“)

and

also

offers

his

hand

to

the

actor

(image

4),

the

greeting

now

requires

the

actor‘s

haptic

resource

in

addition

to

his

verbal

and

visual

ones:

he

can

now

no

longer

hold

the

smartphone

with

his

right

hand

and

decides

to

let

it

slide

onto

the

table

and

join

in

the

hand

greeting.

Thus,

no

physical

resource

now

remains

in

the

surfing

activity.

It

is

treated

as

aborted

by

the

interactants.

In

my

data,

it

appears

that

aborted

activities

are

more

difficult

for

interactants

to

resume,

which

is

why

participants

try

to

pause

activities

rather

than

abort

them.

The

example

shows

that

participants

can

simultaneously

coordinate

two

simultaneously

occurring

activities

if

they

use

the

resources

in

a

structurally

compatible

way.

If

activities

behave

in

a

structurally

incompatible

way,

they

are

paused

or

aborted depending on the degree of incompatibility.

What

can

participants

do

when

a

situation

requires

that

two

structurally

incompatible

activities

not

be

aborted

or

paused

but

completed

simultaneously,

for

example,

during

resuscitation as in the introductory example?

Such

situations

can

be

observed

regularly

in

theater

rehearsals

when

scenes

are

being

rehearsed.

In

order

not

to

have

to

start

from

the

beginning

with

every

forgotten

word,

one

of

the

participants

prompts.

This

means

that

if

an

actor/actress

is

stuck

in

the

text

(so

called

blanking

),

the

prompter

recites

the

correct

play

text.

This

requires

the

prompter

to

read

the

actors‘

performance

in

the

script.

How

does

a

prompter

recognize

that

an

actor

is

blanking?

In

the

analyses,

two

regular

features

emerge

in

this

regard.

First,

actors

often

pause

before

blankings.

However,

it

is

not

uncommon

in

the

theater

to

intentionally

insert

dramatic

pauses

to

intensify

the

play.

Thus,

secondly,

in

order

to

distinguish

a

dramatic

pause

from

a

blanking,

the

prompter

must

observe

the

performance.

Since

she

can

only

either

observe

the

play

or

read

along

in

the

script,

the

two

activities

are

structurally

incompatible

with

each

other.

Both

activities,

observing

and

reading

along,

require

the

gaze

as

a

visual

resource.

How

does

a

prompting

person

manage

to

observe

the

performance

and

simultaneously

read-along, despite this structural incompatibility?

To

determine

this,

one

must

record

the

gaze

of

the

prompter.

This

is

achieved

via

so-called

mobile

eye-tracking

glasses,

which

record

the

view

of

the

person

wearing

them.

A

colored

circular

ring

shows

where the person is looking from a subjective perspective.

Figure 2: The assistant director prompts the actor. Image 1 shows the perspective of a camera behind

the director's table. Images 2-4 are taken from the eye-tracking glasses of the assistant director.

The

example

in

Figure

2

shows

the

prompter‘s

gaze

behavior

and

demonstrates

the

compensation

practices

with

which

the

prompter

(left

in

image

1)

deals

with

the

structural

incompatibility

of

the

activities

of

observing

and

reading

along.

In

doing

so,

she

reads

the

script

while

the

actor

(right

in

image

1)

acts

out

the

scene

on

stage

(image

1).

By

analyzing

the

prompter’s

eye-tracking

data

(images

2–4),

we

see

that

she

forms

a

kind

of

grid

with

her

hands

in

order

not

to

lose

her

place

in

the

script

(image

2)

and

reads

what

the

actor

says

in

the

script.

Suddenly,

the

actor

first

pauses

for

0.4

s,

and

then

utters

a

stretched

delay

signal,

äh

.

Since

this

is

an

element

that

is

not

recorded

in

the

script,

the

prompter

looks

up

at

the

actor

(image

3).

Here

she

can

observe

that

the

actor

is

frozen

in

his

play

and

has

stopped

moving.

She

interprets

this

not

as

a

dramatic

pause

but

as

a

situation

in

which

the

actor

is

stuck

in

the

text.

Since

this

must

be

avoided,

she

then

recites

the

missing

text

(“Ich

steh

immer

noch

regungslos

da“).

The

blanking

is

overcome

when

the

actor

picks

up

the

text

and

integrates

it

into

his

performance

(image

4).

At

this

moment,

the

prompter

re-lowers

her

gaze

into

the

script.

As

the

red

eye-tracking

circle

ring

shows,

her

gaze

lands

unerringly

on

her

pencil

as

part

of

the

grid.

This

helps

her

to

quickly

resume

her

read-along

activity

without

having

to search for the right line.

As

this

reconstruction

of

events

shows,

it

is

by

no

means

the

case

that

the

prompter

can

completely

resolve

the

structural

incompatibility

of

the

activities

of

observing

and

reading

along;

she

can

still

either

look

at

the

actor

or

read

the

script.

However,

she

resorts

to

practices

that

compensate

for

the

absence

of

the

visual

resource,

at

least

for

a

short

time.

For

example,

she

reads

along

in

the

script

until

she

gets

a

clue

about

a

text

blanking.

In

all

cases

studied,

these

cues

consist

of

the

pattern

pause

in

speech

and

stretched

delay

signal.

What

is

exciting

about

this

is

that

it

is

neither

a

prearranged

cue

nor

something

that

actors

learn

in

their

training.

Instead,

this

is

an

interactional

negotiation.

The

prompter

only

redirects

her

attention

from

the

script

to

the

actor

when

there

is

a

concrete

indication

of

a

blanking.

If

the

actor

blanks,

she

verbalizes

what

has

just

been

read.

This

means

that

the

prompter

not

only

reads

along,

anticipating

the

words,

but

is

also

able

to

repeat

an

entire

sentence

while

looking

at

the

actor.

In

this

way,

what

is

read

along

is

made

available

in

the

observation.

Since

the

prompter

immediately

resumes

her

read-along

as

the

actor

continues in the text, she minimizes her time not doing so.

Accordingly,

the

coordinative

action

of

the

prompter

is

characterized

by

three

procedures:

a)

routinization,

b)

synchronization, and c) prioritization.

a)

Routinization:

With

the

help

of

the

script,

she

can

predict

the

course

of

the

scene

and

the

future

utterances

of

the

actors, which enables her to read along in

anticipation.

b)

Synchronization:

While

reading

along

with

the

performance,

she

looks

at

the

parts

of

the

text

where

the

actor

could potentially blank.

c)

Prioritization:

She

withdraws

her

visual

resource

from

one

activity

for

a

minimally

short

moment

only

when

there

is

a

need

for

action in the other activity.

Through

these

procedures,

the

prompter

naturally

does

not

manage

to

grow

a

second

pair

of

eyes

or

learns

to

gaze

like

a

chameleon;

however,

she

can

compensate

for

the

absence

of

the

visual

resource

in

such

a

way

that

none

of

the

simultaneously

relevant activities has to be interrupted or paused.

Possible applications

The

analyses

show

that

we

need

certain

structural

conditions

to

perform

more

than

one

activity

simultaneously.

Performing

more

than

one

activity

at

the

same

time

is

possible

if

we

can

divide

our

physical

resources

among

the

activities

(structural

compatibility).

If

two

activities

require

the

same

resource

(for

example,

the

visual

resource

gaze)

to

perform,

they

are

structurally

incompatible.

In

such

instances,

one

of

the

activities

can

be

canceled

or

paused

until

the

resource

is

available

again.

If,

however,

a

situation

requires

that

several

activities

be

realized

simultaneously

despite

structural

incompatibility,

the

lack

of

a

resource

can

be

compensated

for

briefly

with

the

help

of

the

interactional

procedures—routinization,

prioritization,

and synchronization. This phenomenon is called "multiactivity."

As

the

example

of

the

prompter

demonstrates,

it

is

essential

that

she

have

recourse

to

these

techniques

in

order

to

be

able

to

pursue

her

task.

Accordingly,

the

question

arises

as

to

whether

this

knowledge

is

limited

to

prompter

situations

or

whether

there

are no other areas of application.

In

artistic

fields,

the

simultaneity

of

several

activities

always

plays

an

important

role

when

something

is

elaborated

while

it

is

being

done.

In

the

elaboration

of

scenes

(Krug

2020a)

,

something

is

performed

while

it

can

be

commented

on

and,

thus,

changed

at

the

same

time

(Krug

2020b)

.

The

simultaneity

of

activities

is

here

the

structural

precondition

for

creative

work.

Furthermore,

this

applies

to

many

didactic

areas:

in

dance

lessons,

a

dance

can

be

demonstrated

and

explained

at

the

same

time;

in

vocational

inductions,

a

machine

can

be

operated,

and

its

functioning

explained

at

the

same

time;

and

in

school,

an

experiment

can

be

demonstrated,

and

the

physical

laws

behind

it

explained.

In

all

these

examples,

the

simultaneity

of

activities

is

understood

as

an

opportunity to communicate complex relationships.

But

what

happens

when

the

simultaneous

occurrence

of

activities

in

a

situation

poses

a

problem?

We

could

clearly

see

this

in

the

initial

example

of

the

resuscitation

situation:

here,

physicians

have

to

perform

several

activities

simultaneously,

which,

on

the

one

hand,

are

highly

time-critical

but,

on

the

other

hand,

are

not

always

compatible

with

each

other.

As

recent

studies

have

shown,

annually,

only

10%

of

the

approximately

700,000

people

who

suffer

cardiac

arrest

in

Europe

survive

resuscitation

(Gräsner

et

al.

2014)

.

Some

of

these

failed

resuscitation

attempts

are

due

to

problems

in

team

communication

(Castelao

et

al.

2013)

.

An

initial

study

by

Pitsch/Krug/Cleff

(2020)

shows

that

some

of

these

problems

occur

when

team

leaders

instruct

their

team

while

simultaneously

performing

an

often-complex

medical

intervention.

Since

the

activities

are

often

structurally

incompatible,

the

team

leader

faces

a

dilemma:

should

she

instruct

her

team

on

the

next

steps,

which

ensures

the

continuation

of

resuscitation,

but

thereby

risk

suspending

the

patient‘s

ventilation

for

a

short

period

of

time,

which

could

result

in

hypoxia

and

thus

permanent

damage?

In

the

worst

case,

the

team

leader

tries

to

meet

both

requirements

and

fails

twice:

an

improperly

instructed

team

can

prepare

resuscitation

measures

poorly,

and

a

failure

to

treat the patient can have fatal consequences.

Using

the

model

of

structural

compatibility

presented

here,

such

communicative

problems

can

be

systematically

identified,

described,

and

dealt

with.

Particularly,

the

model

can

support

medical

(and

other)

professionals

in

distributing

tasks

in

such

a

way

that

only

compatible

activities

have

to

be

realized

at

the

same

time.

The

model

thus

provides,

for

example,

a

structural